Chapter One

The Martyrs’ wives building

(2012-2014)

At first, the people said revolution! Ordinary men – transformed – became freedom fighters. With such romantic hope and expectation mounting in parts of Syria in 2011, women fell in love with their husbands anew.

When, in 2012, we first met these members of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), as they plotted revolution in Syria from the safety of Amman, Jordan. All we saw of their wives was a hand deftly offering us visitors trays of coffee and tea.

But then, one by one, their men died. Some said, so too did the revolution. The protracted fighting had taken a dark and then darker turn. Fighters came from outside of Syria, factions proliferated, and soon, the idealism of the early days of uprising had all but disappeared.

As it became clear that the Syrian regime would survive, countries like Jordan, that had hosted opposition fighters and their families – soon to become their survivors – grew less welcoming.

The 654,582 registered Syrian refugees in Jordan live both in designated camps and in the cities, in whatever housing their means will allow. For the women in this chapter, who have lost their husbands to a war for a country to which they cannot return, home is now the martyrs’ wives buildings.

More

Why did you leave me when I needed you?

Aysha, 31, has been widowed for four years after eleven years of marriage to Abu Layla, a fighter in Daraa. Here, she shows a tattoo on her shoulder that reads, “Why did you leave me when I needed you?” It relates to a dramatic quarrel the young teens had when secretly dating – upon making up, they each had the tattoo made as a reminder of how horrible it was being apart. Aysha never imagined the tattoo would take on such a dramatically different meaning years later.

Aysha’s daughters during a heat wave, stuck in the apartment, windows yielding little breeze. Before the conflict, 94 percent of Syrians attended primary or lower secondary school, by June 2017, 43 percent of Syrian refugees are now out of school. Many of these include girls living in Jordanian cities, who upon reaching puberty, are kept at home due to fears for their safety and of sexual harassment. The women’s fear is rooted in being outsiders in the places in which they have taken refuge. They worry that strangers from another country (not their own) will not protect their daughters; some feel outright preyed upon.(photographed 2012)

When Abu Layla was alive, he would send Aysha sultry texts, poems, and images from the front lines. It was by text message she found out that he was killed while fighting in Syria. When her old Nokia died, she lost her trove of memories. This is the only image she has from that time before his death. (photographed 2012)

Seven miles to the Syrian border. View from Jordan’s highway to Ramtha, one of the most populous Syrian refugee communities.

In her sleep

Layla, 13, (right) and Sama, 15, (left) stand for a portrait weeks after finding out their father had been killed in Syria. At the news of his death, their mother was pregnant with her sixth child. Barely widowed, she was under almost immediate pressure to marry off her two eldest daughters. She resisted and found refuge in Aysha’s building. Layla remains shell-shocked after being trampled upon in her sleep by an entire Syrian regime unit. They stormed her house in Daraa searching for her father just before the family fled to Jordan in 2012.

Children were an exception to the fear of being identified in a photograph. Layla fell just shy of the age of being inappropriate to photograph. That changed the following year, when her face, too, needed to be obscured.(photographed 2013)

< Drag the arrows on the image left and right >

In 2013, Um Salim (mother of Layla and Sama) shared a mobile phone image of her martyred FSA husband. She received the news of his death by text while about to deliver her baby. She did not see his body, only a gruesome image of his dead body in a funeral shroud.

She had received this romantic image from her husband just weeks before his death, and framed it with reverential words of his martyrdom, now a digital memorial.

Today she is living in a martyrs’ wives building in Ramtha, Jordan.

Two years later, 15-year-old Layla ‘celebrated’ her 17-year-old sister’s marriage. She feels alone now, and knows most likely her near future holds a marriage. Her mother has six kids and barely survives by living in a martyrs’ wives building. Um Salim is under constant pressure to marry off her daughters to Jordanian and Syrian suitors. Layla dreamt of finishing high school and becoming a teacher when I first met her. She stays at home now, day in and day out (the mothers do not feel safe to send their teen girls out on their own to school).

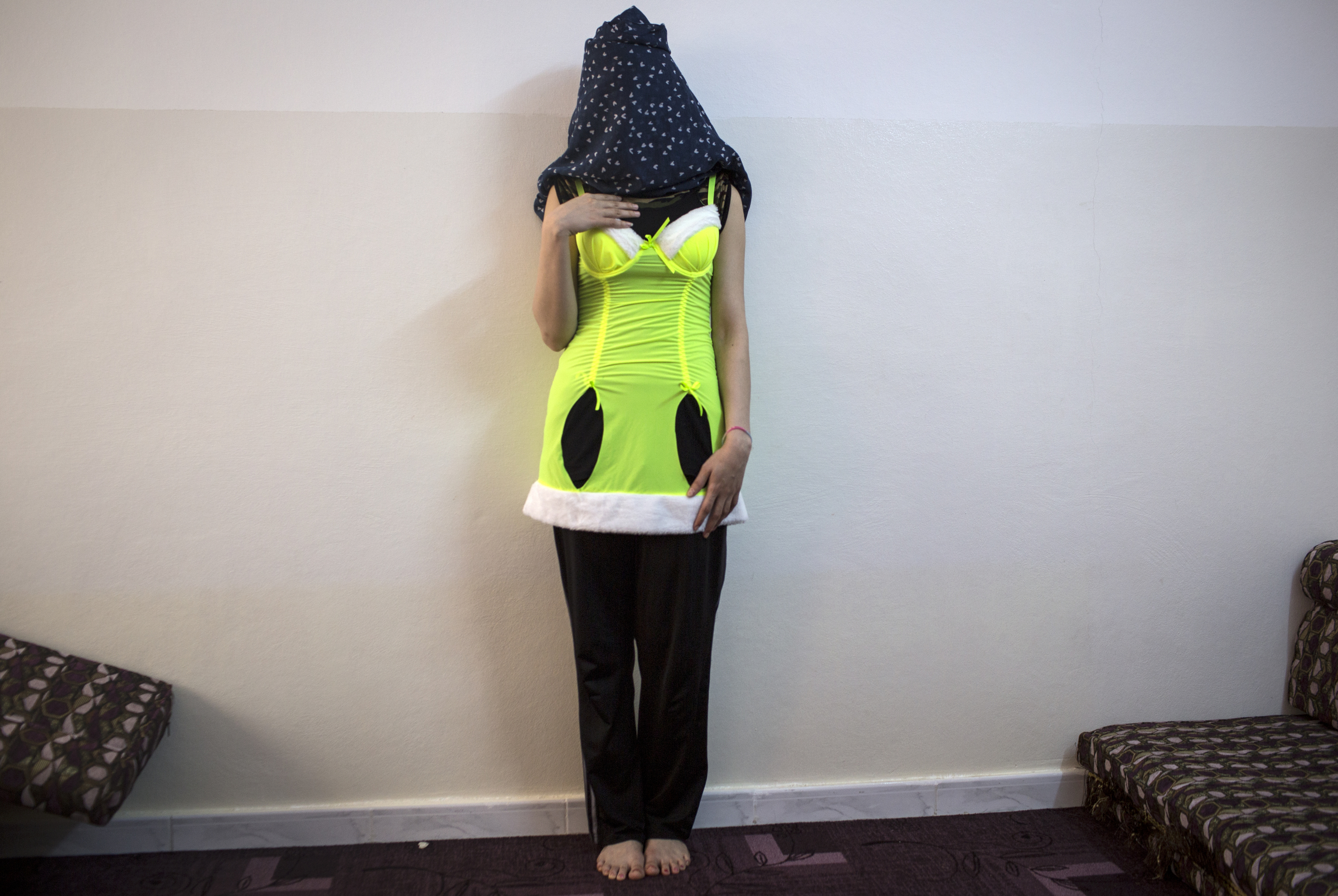

Hala, another young neighbor, also ‘celebrates’ her sister’s wedding, jovially trying on her wedding night negligee. A divorcee at 18, after only twenty-five days of marriage, Hala was forced to marry her abusive cousin after her father was killed in their hometown of Daraa. Now 19, Hala is about to see her younger sister marry a Syrian man she’s met only three times in two weeks.

She breaks the crippling boredom of her unrelenting confinement by writing poetry.

“Do not expect me to get married like my sister. I want someone to fall in love with,” Hala insisted the day this photo was taken at the start of summer. By the end of the season, she was considering a proposal from a Saudi who she had yet to meet in person, tired of wasting her days staring at same four walls and “slowly dying.” (photographed 2013)

Two years later, Hala poses as a “Kung Fu princess.” The marriage with the Saudi never materialized. He had wanted Hala as a second wife, to take care of his sick first wife and their children. To Hala’s relief, he eventually lost interest in the logistics of bringing her to Saudi Arabia.

(photographed 2015)

Martyrs’ wives building resident Um Mohamud, 35, had little room in her Peugeot as she fled Daraa with her five children, following the death of her fighter husband in their native city. She managed to stop long enough to film her house, thinking she might never see it again. Indeed, it was bombed a few months later. The only sentimental item she took was a wooden tray her husband had bought her on a trip to Beirut. Now, she lives on donations and charity as a “wife of a martyr.” Her phone since died, and she lost the entire trove of memories of the life she had in Syria and the man she loved. (photographed 2013)

The martyrs’ wives were once called rebel wives. Back then, they would swap tips about how best to entice their husbands once reunited. On this day, as the women lamented their weight gain from eating junk food and being trapped indoors, one woman cried that she had left with the clothes on her back and had no lingerie. An aging grandmother proudly emerged with this negligee, offering to share it. The younger women placated her, chuckling quietly to themselves.

Aysha advises: “A sexy bra and panties is better than a negligee when he comes home. Highlight your hair and wear a red dress.”

This was a short-lived period, as the lexicon of war changed, and words like “revolution” and “freedom fighter” were replaced with far more ominous realities, such as “loveless marriage” and in some cases, “abuse.” (photographed 2012)

Once her crowning glory

Poet Hala’s grandmother, 88, brushes her vibrantly dyed hair, once her crowning glory. Her son died fighting in Syria. She had advised him on his wedding night to slap his new wife once, to assert his authority. Despite that abrupt beginning, the marriage had been a happy one until his death. Her granddaughters are respectful but quietly laugh at the elderly woman’s advice about how women should live. She died one year after this photo was made, a Syrian refugee in Jordan. (photographed 2013)

Selene (Hala’s mother, 36) keeps her husband’s favorite white slacks, fantasizing he will return. Despite that wedding night slap, at his mother’s behest, it was a happy marriage. He was missing for seven months in Syria before Selene learned of his fate. She refused to see the digital images marking his death. He was killed by a sniper in Daraa while fighting with the FSA, leaving Selene with six children. She jokes with her fellow widows that if he comes back, she will share him in the evenings. Selene is the most optimistic resident in her martyrs’ wives building, noting how much worse she believes life is in the refugee camps. She deeply loved her husband and is struggling to make a future for her children. Selene is desperate to find a husband for her divorced eldest daughter, pragmatically feeling it is the only hope Hala has for a future.

Satellite news depicts a martyr from the Syrian Civil War. Such images are ubiquitous on television sets and mobile phones of Syrian refugees in Jordan.